In fact whatever unfulfilled and unfulfillable obligation [my father] felt was less identifiable than that. There was about [my father] a sadness so pervasive that it colored even those many moments when he seemed to be having a good time. He had many friends. He played golf, he played tennis, he played poker, he seemed to enjoy parties. Yet he could be in the middle of a party at our own house, sitting at the piano — playing “Darktown Stutter’s Ball,” say, or “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” a bourbon highball always within reach — and the tension he transmitted would be so great that I would have to leave, run to my room and close the door. — Joan Didion, Where I Was From (2003)

At least some of the time, the world appears to me as a painting by Hieronymous Bosch; were I to follow my conscience then, it would lead me out onto the desert… praying, as if for rain, that it would happen: “…let it come and clear the rot and the stench and the stink, let it come for all of everywhere, just so it comes and the world stands clear in the white dead dawn.” — Joan Didion, “On Morality” (1965)

Wagon-train Morality. “For better or for worse, we are what we learned as children.” So says Joan Didion in her 1965 essay “On Morality.” Let’s have a look, then, at some of the lessons she absorbed in her youth.

When Didion could tell her father’s conscience was troubled by an amorphous but deeply felt obligation to his family, she would run to her room and close the door. She was haunted by his unresolved moral tension but couldn’t help inheriting it, and she never shed the impulse to run from it. As an adult, instead of closing the door on her father’s pervasive sadness, she would shut it on the world when it seemed a Boschian hellscape. She would escape to a desert in her mind, pray for biblical flood, and dream of the “white dead dawn.”

Didion was also “chilled to the bone” by her mother’s five-word refrain “what difference does it make,” a phrase which Didion described in Where I Was From as a “barricade against some deep apprehension of meaninglessness.” And yet her mother’s defensive nihilism lodged itself in Didion’s soul, a stopgap sitting uneasily inside the void left open by her father’s unresolved tension. At least, these are the aspects of her upbringing that shine through in “On Morality.”

I’ve put it a bit too passively with the phrase “shine through.” We know from “Why I Write” that Didion sees writing as “an aggressive, even a hostile act,” the “tactic of a secret bully” who’s bent on “imposing [her] sensibility on the reader’s most private space.” In keeping with this view, “On Morality” is a hostile essay written not by a run-of-the-mill bully, but a master of emotional manipulation.

Didion’s central claim in the piece is that “the ideal good” is not a “knowable quantity.” We cannot know right and wrong, good and evil, beyond a “primitive level.” We must honor our “loyalties to those we love.” We do so by upholding “a code that has as its point only survival, not the attainment of the ideal good.” When we extend morality beyond this primitive loyalty — when we start to judge “all the ad hoc committees, all the picket lines, all the brave signatures in The New York Times” by the standards of virtue and vice — “then is when the thin whine of hysteria is heard in the land, and then is when we are in bad trouble.”

Knowing that her position is unpalatable, she whets your appetite with sexy prose and shellshocks you with a barrage of brutal imagery. By the end of the first paragraph, you’re picturing a disaffected cool girl sweating it out in a Death Valley motel room, ice cubes melting down the small of her back:

As it happens I am in Death Valley, in a room at the Enterprise Motel and Trailer Park, and it is July, and it is hot. In fact it is 119 degrees. I cannot seem to make the air conditioner work, but there is a small refrigerator, and I can wrap ice cubes in a towel and hold them against the small of my back. With the help of the ice cubes I have been trying to think, because The American Scholar asked me to, in some abstract way about “morality,” a word I distrust more every day, but my mind veers inflexibly toward the particular.

There’s nothing sexy about abstract morality, but everything about this paragraph is sexy. “I distrust the very idea of morality, but this well-renowned magazine is paying me to write about it, so fuck it, I’ll bite. Good thing I have these ice cubes, because it’s so hot in here, I wouldn’t even be able to focus if I didn’t have them pressed against my sweaty little back.” (Lol, you might be thinking, nice. Classic sexist move, Nick, way to sexualize a woman’s writing instead of addressing its substance. To which I respond: bullshit. We both know what game Didion was playing here, and in any case, I’m getting to the substance.)

Now for the barrage of brutal imagery. The “particulars” toward which Didion’s mind veers inflexibly are some recent tragedies that struck the Valley:

A teenage boy driving drunk crashes on the desert highway, killing himself and injuring his girlfriend. A nurse arrives, drives the girl to the hospital, and leaves her husband with the dead boy overnight, trusting him to keep the coyotes from tearing the corpse apart.

A pregnant eighteen-year-old stares for days on end at the surface of a lake in which her husband drowned. She watches as a team of divers tries to retrieve the body, but they can find no bottom to the lake and no trace of her husband, only “the black 90-degree water going down and down and down, and a single translucent fish, not classified.”

These anecdotes are meant to rattle you. It’s the world as Boschian hellscape, merciless and gory and absurd. She tells us of an American intellectual who, as a child, declared to his rabbi that he did not believe in God, only for the rabbi to respond: “Tell me, do you think God cares?” The upshot of all this is: we’re born into a cruel, indifferent universe to suffer and die. If we’re lucky, if we honor the primitive social code, then maybe the black, bottomless desert water won’t take us, and the coyotes won’t rip the flesh from our bones. In the meantime, we’ll drive from bar to bar to swap horror stories about the ones who didn’t make it, or gather to sing prayer hymns in unison to conceal the tone of death in our voices.

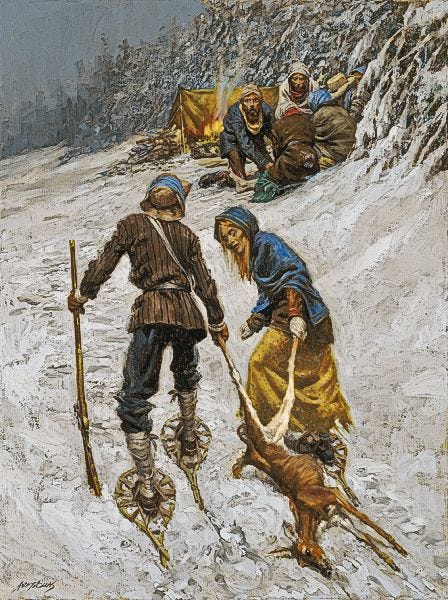

Didion was raised on the crossing story — the fountainhead of wagon-train morality — her ancestors having traveled from the Appalachians to Arkansas and on to the Oregon Territory. They went partway with the Donner Party but split off on their own before the winter of 1846, during which the Sierra Nevada snowfall famously drove some of the travelers to cannibalism. Didion was taught to think the Donner Party suffered not from a tragic turn of fate, but from the consequences of their own failure. They wouldn’t have been trapped by mountain winter unless they “had somewhere abdicated their responsibilities, somehow breached their primary loyalties.” They broke the code, then starved and froze.

Didion is trying to shock her reader into submission. She wants you wide-eyed and slack-jawed, moving without pause from ravenous coyotes and pregnant widows and starving pioneers on to a discussion of fundamental morality. In fact, she needs you that way, because the discussion itself is shallow and unpersuasive.

Didion tells us she distrusts all but wagon-train morality, a social code geared only toward survival. This morality demands of us only loyalty — to our loved ones and to the code. We can be sure that this loyalty is “right” and “good,” that its absence is “wrong” and “evil.” But beyond the immediate circle of those we love, with respect to any decision not bound by the primitive code, the concepts of right and wrong are meaningless, because the ideal good is unknowable. She asks, “Except on that most primitive level — our loyalties to those we love — what could be more arrogant than to claim the primacy of personal conscience?” It’s a hypothetical question to which the answer is nothing, and it bullies the reader into feeling arrogant for disagreeing with Didion’s central argument.

But her central argument begs quite a few questions. Where do we draw the line between the circle of those we love and the strangers who don’t make the cut? What if the social code meant to ensure the survival of that circle is flawed? Is everything beyond that code — all the ad hoc committees and picket lines — wholly separable from our survival? And why is it any less arrogant to claim primacy of personal conscience on the primitive level than to do so beyond it?

Drawing the line. In Where I Was From, Didion quotes a passage from a crossing journal, dated to 1849. On the trail, Bernard Reid saw “an emigrant wagon apparently abandoned by its owners” and “a rude head-board indicating a new grave.” Beneath the headboard were buried Robert and Mary Gilmore, a husband and wife who’d died of cholera on their way to California. Turning his attention from the headboard to the abandoned wagon, Reid was “surprised to see a neatly dressed girl of about 17, sitting on the wagon tongue, her feet resting on the grass, and her eyes apparently directed at vacancy.” He goes on:

She seemed like one dazed or in a dream and did not seem to notice me till I spoke to her. I then learned from her in reply to my questions that she was Miss Gilmore, whose parents had died two days before; that her brother, younger than herself, was sick in the wagon, probably with cholera; that their oxen were lost or stolen by the Indians; and that the train they had been traveling with, after waiting for three days on account of the sickness and death of the parents, had gone on that morning, fearful, if they delayed longer, of being caught by winter in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Now imagine yourself as a member of the caravan who left Miss Gilmore behind. Perhaps you’d heard of the horrors suffered three years prior by the Donner Party. And yet you stayed with Miss Gilmore for three excruciating life-or-death days. You stayed because Miss Gilmore was part of the circle to which loyalty was owed. But the longer you waited, the more you questioned the boundaries of that circle. She wasn’t your kid. Maybe she wasn’t even your niece. She was, let’s say, your second-cousin’s daughter. Sure, you were at her baptism, and you babysat her from time to time, and she came to you for advice when she had her first period. But, hell, the clock was ticking, and the lives of your actual daughter and your actual niece were at risk. On the second day someone speaks up and says the caravan should go on without her. You push back, moved by pure nostalgia. But that night the Donner Party visits you in your dreams, and you can’t bear the thought of putting your daughter through that nightmare. On the third day you second the motion, and then the group puts it to a vote. By a narrow margin, the group decides to push ahead. On Monday, Miss Gilmore made the cut; then the boundary of the circle shifted. By Thursday, she was left for dead.

In Where I Was From, Didion asks, “When you survive at the cost of Miss Gilmore, do you survive at all?” She doesn’t answer, and I don’t know how she would answer. She’s exposed a serious moral ambiguity here, one that lives at the “most primitive level” she once saw as an exception to the rule of unknowable morality.

Pinpointing flaws. If survival is the only point of wagon-train morality, then line one of the code should read: Do not board the wagon. Because no matter how bad life is at home, it can’t be worse than winter in the Sierra Nevada. But that’s not line one of the code, and this calls the rest of it into question. The idea here is that, if your social code is meant to ensure survival, but the code is flawed, then loyalty to it is in fact suicidal. In Where I Was From, Didion highlights plenty of flaws in the social code she was raised on — flaws in spite of which Californians maintained their loyalty, and because of which their survival is now threatened.

The pioneers traversed a vast, harsh wilderness to reach California, and once there, they came face to face with “grandiose landscapes” — giant redwoods, Big Sur, the “great vistas” of Yosemite. Didion shows how Californians felt dwarfed by the “mighty” nature they inhabited:

Scaled against Yosemite, or against the view through the Gate of the Pacific trembling on its tectonic plates, the slightest shift of which could and with some regularity did destroy the works of man in a millisecond, all human beings were of course but as worms, their “heroic imperatives” finally futile, their philosophical inquiries in vain.

Feeling dwarfed by their environment and desperate to manifest the better life they came to it in search of, Californians lost no sleep over dramatically reshaping it. They built dams, diverted snowmelt and mountain runoff into intricate irrigation systems, and transformed deserts into productive farmland and seasonal shallow seas into fertile valleys. These changes enabled the emergence of a massive agricultural economy, one which lives on to this day, and one which is increasingly threatened by a man-made water shortage. And so, Californians — who “did not believe that history could bloody the land, or even touch it” — created a threat to their livelihood by doing exactly what Didion’s primitive morality said would ensure survival: they remained loyal to the social code.

Again, moral ambiguity creeps in at the primitive level Didion took for granted in “On Morality.” Blind loyalty doesn’t cut it; we must interrogate the social codes we inherit, because it turns out they can be fatally flawed.

Beyond the code. Didion declares that questions of public policy, ad hoc congressional committees, picket line protests — these things lie beyond the realm of primitive morality, beyond the social code and circle of loved ones to which we owe loyalty. And, again, we can find in Where I Was From specific examples that complicate the view espoused in “On Morality.” Take her reporting on Lakewood, California, for example.

Lakewood was Levittown on steroids — a planned post-war community in Southern California with 17,500 houses built around a 256-acre retail complex, America’s largest at the time. The town’s rapid rise was enabled by “the perfect synergy of time and place, the seamless confluence of World War Two and the Korean War and the G.I. Bill and the defense contracts that began to flood Southern California as the Cold War set in.” Didion quotes Donald Waldie, the town’s public information officer, who she interviewed in the 90s for her piece “Trouble in Lakewood”:

Naively, you could say that Lakewood was the American dream made affordable for a generation of industrial workers who in the preceding generation could never aspire to that kind of ownership… They were oriented to aerospace. They worked for Hughes, they worked for Douglas… They worked, in other words, at all the places that exemplified the bright future that California was supposed to be.”

Except that future, and this new class of homeowners in Lakewood, were entirely dependent upon the defense contracts that kept the Hughes and Douglas plants running. For forty years the town was sustained “by good times and the good will of the federal government.” During that time, Lakewood was “America, USA.” Youth sports were the pride of the town. Uncles would bring dozens of coworkers from the factory lines out for their nephew’s little league games. The schools churned out good citizens. Then the luck ran out.

The contracts dried up, and the factories closed down. And the social fabric of Lakewood wore thin. The decline was most visible in the town’s Spur Posse controversy, which garnered national attention. A bunch of high school aged boys were accused of raping girls their age and younger — one a mere ten years old. Many residents brushed the whole affair off as routine teenage drama blown out of proportion by a sensationalist national media. If the rape allegations weren’t enough to convince them something was afoot, the pipe bomb did the trick. A mother of one of the Spur Posse boys finally conceded that “the wrecking ball shot right through the mantel and the house has crumbled.” This kind of chaos was inversely correlated with aerospace industry layoffs. As Didion put it:

This is what it costs to create and maintain an artificial ownership class.

This is what happens when that class stops being useful.

But let’s rewind for a moment, back before the Spur Posse started wreaking havoc, back to the days when it first became noticeable to astute observers that the defense contracts propping up Lakewood might soon disappear. If those observers had begun lobbying their congressional representatives, asking for an ad hoc committee on the future of Southern California’s aerospace industry, would they not have been doing precisely what primitive loyalty required of them? They would have. The same would’ve been true if they formed picket lines outside the Hughes and Douglas plants after the first rounds of layoffs. They’d have been fighting for their livelihoods, fighting to keep food on the table for their families, fighting for the very existence of the town that was home to all their loved ones.

And suddenly Didion’s neat division between the “most primitive level” and all the rest has gone up in smoke. National concerns are local concerns. Ambiguity permeates all.

Unknowable quantities. In “On Morality” Didion wants us to accept that the particular is knowable whereas the abstract is not. We can know right and wrong in matters of primitive morality, but can make no claim to the ideal good. Her argument overlooks the many ambiguities I’ve exposed here. Primitive morality is not so straight forward. We must make decisions about who belongs in the circle of those we love, and who is a stranger we can cast aside. We must interrogate the social codes we inherit, even when their only stated point is survival, because loyalty to a flawed code spells disaster. And we cannot easily differentiate between the particular and the abstract, the primitive and all the rest. Hence the unresolved moral tension that Didion’s father transmitted, the pervasive sadness that shone through even on joyous occasions. His concern was primitive loyalty, yet his mind was not at ease.

We cannot escape the burden of moral ambiguity. Didion was right that it’s arrogant to claim primacy of personal conscience. But she was wrong to cast it aside after recognizing it as unclaimable. Primacy of personal conscience — the most perfect knowledge of the good, abstract and particular — is a goal we should always strive for, knowing we’ll never reach it. There are degrees of knowledge. We can accrue wisdom. It’s not when we extend morality beyond the most primitive level that we’re in “bad trouble” — it’s when we grow weary of perpetual doubt, and give in to the lust for certainty. Either we strive earnestly in the face of uncertainty, or we wind up flying blind. Or we shut the door in nihilistic self-defense, and lie in wait, dreaming of the white dead dawn.

Hell, I wrote this and stand by it, but I’m still a Didion fanboy. Thanks so much, though. And we’re mutually stoked!

That was so brilliant and thorough. You changed my mind, even as a Didion fangirl. Also stoked to see another Philadelphian on Substack :)