The Aspirations of the Spirit

An encounter at a bookstore, a false (?) dichotomy, an assassination attempt, and some personal news

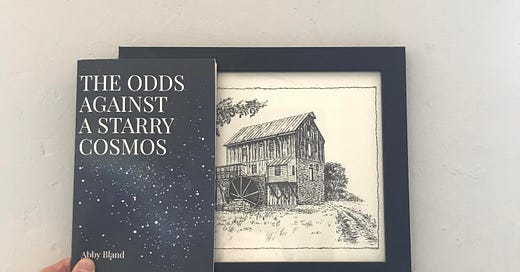

On a Saturday in January, while perusing the shelves of a South Philly bookstore, I overheard the girl behind the counter say, while ringing up a customer, “I wrote this — would you like me to sign it?” I don’t know the girl’s name or the title of the book she wrote; it didn’t occur to me to ask her when I went up to pay for a collection of poems titled The Odds Against a Starry Cosmos. 14 poems, 21 pages. I read them all that night, and then the ones that moved me most again on Sunday.

And then I got to thinking. Here I am reading a small press book that I plucked off of a shelf in South Philly almost at random, written by someone “with a B.A. in English from William Jewell College” who now directs the “Kansas City Poetry Slam and Poetic Underground Open Mic,” and I’m blown away by it. It was one of hundreds of books containing thousands of poems in that bookstore, all or almost all of which I’ll never read. And it was sold to me by another someone who wrote another book that I’ll also likely never read.

How many of those books would blow me away if only I made the time to read them? How many books would’ve blown me except they were lost to the sands of time, or were never made public, or were conceived but never written? Beyond books — what about paintings, sculptures, buildings, songs, plays, athletic performances, speeches? How many profound products of the human spirit will we never get the chance to cherish? And what if one of them was created by that girl behind the counter, the one who mumbled “welcome in” when you walked through the door of whatever little shop you visited the other day?

I was humbled by this train of thought, and then I tagged those who inspired it in a tweet:

By Monday, the poet, the bookstore, and the publisher had all seen and responded to my tweet:

Our world is chock-full of incredible people capable of incredible things. The internet — for all the havoc it’s wrought — is a luxury that, used well, can enhance our experience of the world, our interactions with the people in it, and our enjoyment of their creations. But being connected to so many people saying and doing so many things can be overwhelming: The Batman just came out and so did Elden Ring, Canadian truckers are blockading and Russian troops are invading, students are shouting down administrators at Yale Law School, Lyndsay Graham is pining for Putin’s assassination, Tom Brady is retiring (sike false alarm), Elon Musk is sending Starlink to Ukraine, Jake Paul offered Kanye West and Pete Davidson $30 million a piece to box each other, maybe he should make the same offer to Chris Rock and Will Smith… oh, and the Wordle today was really hard, how many tries did it take you?

We’re surrounded by an endless sea of information. It can make us feel small and the things we do seem insignificant. Experienced this way, modern information technology is rather like our physical universe — if that universe is understood from a certain scientific/rationalistic/atheistic perspective, a perspective from which human life can appear trivial, playing out as it does on a tiny little planet orbiting an unimpressive star in some obscure corner of one galaxy among the billions known to exist. Of course, that perspective isn’t the only one from which to understand our physical universe, but all too often it’s framed as one of only two general viable options: there are the godless worldviews that makes us feel small and insignificant, and then there are the ones that admit a god or gods, and those ones can fill us with a sense of dignity.

Yesterday, an essay of mine — inspired by the collection of poems I bought back in January — was published by Front Porch Republic. In it, I’ve tried my best to begin articulating an alternative to those two options — one that helps us to feel significant in spite of our smallness without looking to any god (at least in the traditional sense of the word) for assistance. I’m always interested in such alternatives — whether it’s a worldview that circumvents the dichotomy between atheism and religion, or a method of navigating our information environment that avoids the internet’s pitfalls without unplugging from it altogether. I’m far from finding a satisfactory version of either of these things, but I’m also far from done searching. And something uncanny happened while I was exchanging emails with Jeff Bilbro (Editor-in-Chief of Front Porch Republic) about my essay that reinforced my motivation to keep chipping away at these problems.

While I was working on some edits Jeff requested, an activist in Kentucky attempted to shoot a Louisville mayoral candidate. I was reading a story on it, and my curiosity was piqued by a link to a recent blog post written by the shooter. Here’s a quote from that blog post, published about two weeks before I bought The Odds Against a Starry Cosmos:

Many of our friends are suffering from a deep feeling of alienation. They have accepted the belief that we live on this little planet in a solar system on the edge of a galaxy — a minor galaxy — and concede, “Ah, well — we really are unimportant after all. God isn’t there and he doesn’t love us, our government doesn’t love us, our neighbor doesn’t love us and nature doesn’t give a damn.

The sense that we live in a godless universe in which we’re small and unimportant is out there, and it’s troubling for people, and it has consequences. And yet, in the twenty-first century, I think it’s inevitable that a lot of people — myself included — are going to fall short of traditional religious faith. Further exacerbating the alienation are our increasingly online lifestyles, and yet I also think it’s inevitable that we’ll continue to live online as much or more than we already do. That said, we’d better start figuring out, not merely how to cope with these realities, but how to flourish in the face of them. Along the way, we’d do well to keep in mind the following, from the first volume of Perry Miller’s The New England Mind:

Solutions which pass lightly over the uncomfortable or ignore intractable realities are doomed to failure; so also are those which give insubstantial answers to the aspirations of the spirit.