MSG in the Temple of Liberty

Michael Jordan and the lust for greatness // the urban crisis and the (other) end of history

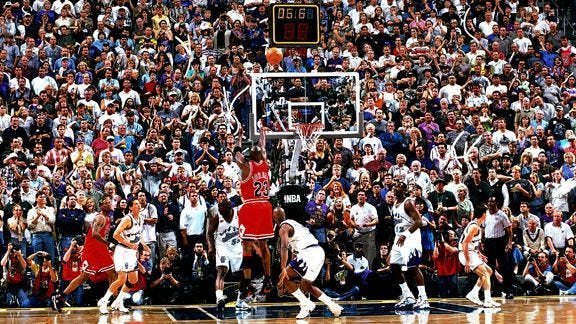

Lust. Michael Jordan is the GOAT. Alpha of alphas. His Airness. Black Jesus. That he asserted dominance by way of basketball is besides the point; the dominance was the point. Hitting the links, playing blackjack, competing with Reebok for brand supremacy at the Olympics, or tossing quarters with security guards, Jordan had to win. No matter the circumstance, no matter the cost. Win.

When he was little, Jordan wanted to be a professional baseball player. He wound up being better at basketball, and so basketball became the outlet for his ambition. When he came of age in the 1980s, basketball giants walked the earth. Magic Johnson and Larry Bird were the best players on the planet, and in them, a new form was starting to take shape: the NBA superstar. Johnson and Bird got the ball rolling, setting the league on its course from ripping-cigs-at-halftime to Dream Team global glory.

But, let’s be honest, before Jordan, the form was far from complete:

Jordan was drafted third overall in 1984 and was widely touted as a rare talent. That earned him a measly $500,000 first-year salary and a $250,000 endorsement deal with an obscure startup — better known for manufacturing track shoes — called Nike. With a little help from his agent, who set out to create a brand around the player rather than using the player to support the brand, His Airness was beginning what would prove to be a long and difficult ascent to the throne:

Not long after the Air Jordan I was released, MJ was wearing them while soaring the skies, giving credibility to the image Nike was helping bring to life:

He established himself as the most talented player in the league long before he won his first championship. Even Bird and Magic were in awe of his athletic prowess. But for the duration of the 1980s, that’s all Jordan was: a freak athlete amassing individual accolades, wealth, and fame. Bird and Magic, while lacking Jordan’s raw ability on the court and his swagger and charisma off it, were winners. They were competing with each other for the title of best player on the best team in the world. Jordan was scratching at the door, but he didn’t yet have a seat at the table.

Thing is, Jordan didn’t want a seat at the table. He wanted a damn throne. And he wasn’t going to stop until he got it. In 1991, he won his first championship. He won again in ‘92. Having won back-to-back titles, he could now sit down with Magic and Bird. But he couldn’t claim supremacy over them — not yet. Then came the Dream Team, and its legendary scrimmage in Monte Carlo:

Jordan had finally climbed a step above the rest. He cemented his position by winning a third straight title in ‘93 — something no one had ever done before and no one has done since (except him, from ‘96 to ‘98). Jordan won six championships by being singularly focused on greatness — day in, day out, without fail. Sure, he had other-worldly natural abilities. But his greatest gift of all was his unshakeable determination. When he says win at any cost, he means it.

Jordan outworked everyone around him. Reggie Miller called him a vampire as an expression of awe at his seemingly inexhaustible energy. When the Pistons beat the shit out of him game after game in the late 80s, he spent the summer in the weight room so that he could dish it out right back. When his teammates didn’t perform to his standards of excellence, he berated them. Sometimes the confrontations turned physical. In pursuit of greatness, Jordan blurred the line between leader and tyrant, leading by fear when setting an example wouldn’t do. But everything he did, he did for the sake of distinguishing himself from the competition. What drove Jordan was an insatiable desire to be on top.

Yes, he loved the game of basketball. But more than anything he loved winning. And that’s why his competitive drive spilled over into other aspects of his life. He wanted the coolest shoes and the hottest endorsements. He wanted little kids to look up to him. Hence Space Jam. Hence “Be Like Mike.”

By the time this commercial aired, Jordan had taken the form birthed by Magic and Bird to its logical extreme. He wasn’t a superstar, he was the superstar. No matter where he went, he couldn’t leave his room without attracting a horde of reporters. All eyes were on him. He was the most popular man on the planet.

Jordan created this spotlight. It didn’t exist — not like this, not in the NBA — before he rose to superstardom. Never before had a basketball player been so universally looked up to, like superman. Sure, Jordan had the benefit of his agent, and the market-reach of all the multinational corporations that endorsed him, and the full backing of the league, which stood to profit profoundly off of his fame. But the smoke and mirrors didn’t create the superstar; they only amplified him. To be celebrated as the GOAT, Jordan had to actually be the GOAT, and he couldn’t afford to leave any room for doubt. If that meant punching a teammate in the face during practice, so be it. He had to be at his best every second of every day, and he had to demand the same from those around him.

If winning has a price, Jordan paid it both on and off the court, because his drive to win wasn’t bounded by the hardwood. He didn’t just have to be disciplined in training and perfect on the court. He had to be flawless in front of the camera, and the camera was always on him. Jordan was more than just the greatest basketball player of all time; he was a global cultural phenomenon. He was the superstar of superstars. Eventually it came time to reap what he sowed.

I wouldn’t want to Be Like Mike. It’s an impossible task.

By the end of his career, Jordan was fatigued by fame and ready to retire — but only because he had achieved what he needed to achieve to cement his legacy. Had he not silenced all debate about who was the greatest player to ever live, he wouldn’t have been able to step away. And yet, he also wouldn’t have needed to. His greatness on the court and his fame off it were inseparable. They were two edges of a single sword that was forged in the flames of his ambition. Having realized the greatness latent within him as a young star, Jordan could walk away knowing that in spite of the slogan, no one could ever Be Like Mike.

In fact, the slogan is an oxymoron. Michael Jordan’s essence is a burning desire to transcend the competition, to have his peers bend the knee in unison at the foot of his throne, to go down in history as the greatest of all time — unlike any who came before him or any who’d come after him. To Be Like Mike is to spit upon the notion of being like anyone else. The only way to truly Be Like Mike is to dwarf his accomplishments, redefine the limits of human achievement, and leave him no choice but to cede the throne.

Limits. Jordan’s ambition wasn’t bounded by the hardwood, but it did have bounds. In his eyes, Madison Square Garden was the “Mecca of Basketball.” The biggest stars want to shine on the biggest stage, and Jordan delivered some of his most iconic performances in The Garden. MSG, then, is the symbolic structure that bounded his ambition. If Jordan was the king, The Garden was his castle.

Fitting, then, that Jordan won his first championship in 1991 — the same year that the Soviet Union collapsed. Western onlookers saw in its demise the final triumph of liberalism over the forces of communism and fascism. Francis Fukuyama proclaimed the end of history because, as he saw it, Western liberal democracy had silenced all debate, asserting once and for all its supremacy over alternate forms of government. The Cold War was over and a new era of peace was upon us, a peace secured by the uncontested hegemony of liberalism.

The victory of liberalism — pronounced prematurely or not — was the culmination of events set in motion by the American Revolution. Looking back at the revolutionary generation in 1838, Abraham Lincoln described the system of political institutions that they established as a “Temple of Liberty.” If by 1991 liberal democracy was the king of the world, we might say that its castle was the Temple of Liberty. Michael Jordan, then, was the king of a castle within a castle — he sat atop the throne of MSG within the Temple of Liberty.

Jordan’s ambition, though insatiable, was confined to a narrow domain of human affairs. While he was redefining the limits of the possible on the court, Fukuyama was asserting the impossibility of doing so on the stage of world history. History, in his view, is propelled by the resolution of fundamental contradictions in human life, with each contradiction resolved enabling the more complete satisfaction of human needs. To all would-be successors to the liberal throne, Fukuyama was saying, in effect, you will never Be Like Mike.

The end of history implies the eternal frustration of ambition. Sure, MSG was up for grabs, but with the Temple of Liberty encompassing the planet, all outlets for the pursuit of world-historical greatness were closed off, much to the dismay of those with the unconfined equivalent of Jordan’s insatiability. As Lincoln put it in 1838, fretting over what would come of the Temple of Liberty now that it was firmly established in the New World:

It is to deny, what the history of the world tells us is true, to suppose that men of ambition and talents will not continue to spring up amongst us. And, when they do, they will as naturally seek the gratification of their ruling passion, as others have so done before them. The question then, is, can that gratification be found in supporting and maintaining an edifice that has been erected by others? Most certainly it cannot. Many great and good men sufficiently qualified for any task they should undertake, may ever be found, whose ambition would inspire to nothing beyond a seat in Congress, a gubernatorial or a presidential chair; but such belong not to the family of the lion, or the tribe of the eagle. What! think you these places would satisfy an Alexander, a Caesar, or a Napoleon?--Never! Towering genius disdains a beaten path. It seeks regions hitherto unexplored.--It sees no distinction in adding story to story, upon the monuments of fame, erected to the memory of others. It denies that it is glory enough to serve under any chief. It scorns to tread in the footsteps of any predecessor, however illustrious. It thirsts and burns for distinction; and, if possible, it will have it…

A century after Lincoln voiced these anxieties, the Temple was under vicious assault from precisely such men of towering ambition — Hitler and Stalin — who represented two forces decidedly not content to tread the beaten path of liberalism. The structure withstood their attacks, and today, there’s no comparably formidable opponent in sight. But if attacks on liberal hegemony have weakened, discontent with it has not. The ambitious among us haven’t grown to love their lot; they’ve given up on finding “regions hitherto unexplored.”

Legacy. The birth of Madison Square Garden was the death of Penn Station, the latter of which was demolished in the 1960s to make way for MSG. If Penn Station was “the architectural embodiment of New York’s vaulted ambition,” its demolition was symbolic of a broader loss — that of our culture’s lust for greatness. Sure, The Garden would go on to house the likes of Michael Jordan, but even the world’s greatest basketball player barely rises to the level of world-historical relevance. Penn Station represented a loftier kind of ambition — public and civic-minded — that sought to lead nations, not teams, to glory.

Inside and out, the building was meant to be uplifting and monumental — like the Parthenon on steroids — its train shed and waiting room a skylit symphony of almost overwhelming civic nobility, announcing the entrance to a modern metropolis.

Grand as it was, Penn Station was only the above-ground portion of a far bolder project. By 1882, the Pennsylvania Railroad was the world’s largest railroad run by the world’s largest corporation. But its line only ran as far east as the Hudson River, so its passengers had to take a ferry to reach what was fast becoming the world’s greatest urban center — New York City. Then came Alexander Cassatt.

Cassatt took over as President of the PRR in 1899 and was hellbent on crossing the Hudson. When efforts to construct a bridge failed, some might have waved a white flag. Not Cassatt. While touring Europe, he saw trains that — powered by electricity — could safely run for long stretches underground. So he decided that, if he couldn’t extend his line over the Hudson, he’d bore a tunnel under it.

No matter that nothing like it had ever been done before. Never mind that he already headed the world’s largest company, and that under his leadership profits were soaring, and that probably, the safest way to keep the good times rolling was… well, really, to do anything but stake his legacy and his company’s financial future on a profoundly expensive, risky, and unprecedented feat of engineering.

You see, Cassatt wasn’t satisfied with financial success. Rail travel was the way of the future, New York was the city of the future, and America was the country of the future. His ambition was not merely to keep PRR afloat — it was to be the man responsible for connecting Manhattan to the mainland, and for propelling his nation to new heights of technological prowess and urban dynamism. “Supporting and maintaining an edifice erected by others” was out of the question for him; Cassatt sought regions hitherto unexplored, and he’d do whatever it took to chart them.

If Michael Jordan was willing to punch a teammate on his path to victory, Cassatt was willing to do far worse. Digging a tunnel under a major waterway with primitive technology, no prior mistakes to learn from, and sure as hell no OSHA, was a perilous business. Cassatt was not doing the digging. The dirty work was done by crews of poorly paid laborers — referred to as “sand hogs” — who alternated shifts to keep the digging going around the clock. By the time the tunnels were complete, over a dozen workers had died and countless suffered from “the bends.” One can imagine Cassatt, like Jordan, saying that, hey, greatness has a price. Another “price” Cassatt was willing to pay for greatness was the razing of tenements in Manhattan’s Tenderloin district to make way for Penn Station. Lose a few sandhogs, displace some of the city’s poorest residents — a shame, yes, but nothing Cassatt was going to let keep him from his legacy.

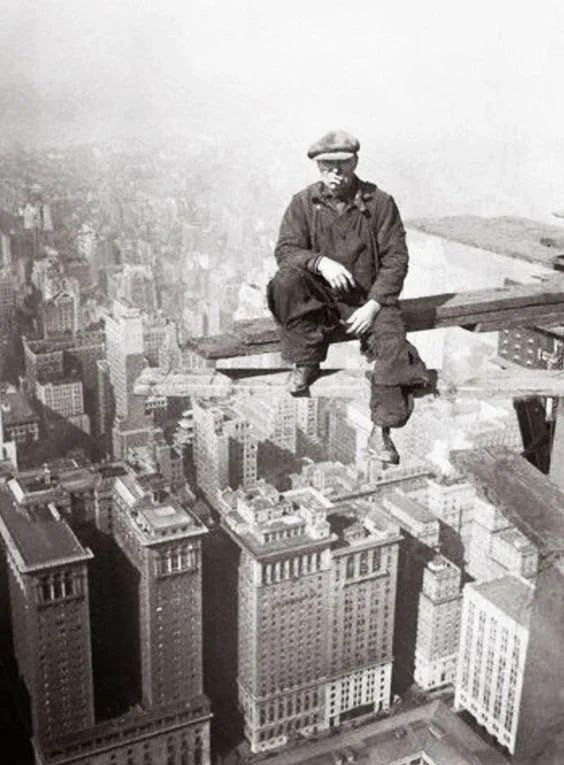

Cassatt, then, helped to bring America into the twentieth century, one defined by rapid technological progress and the rise of the modern metropolis. Doing so required fierce resolve and, at times, a coldness of heart. Perhaps nothing offers a clearer image of this tension at the heart of twentieth-century city-building than the construction of the Empire State Building. Hailed by the press as a “race into the sky,” the project was every bit as bold as Cassatt’s tunnel under the Hudson, and every bit as dangerous. By the time the world’s tallest building was finished, at least five workers — call them “skyhogs” — had fallen to their deaths.

Construction casualties and razed tenements are every bit as much the legacy of American city-building as are Penn Station and the Empire State Building. And the brunt of slum clearing was experienced by African Americans. In 1960s Philadelphia, the phrase “urban renewal is Negro removal” was common currency. Some of our city-builders were explicitly racist; some were merely complicit; some were earnestly interested in countering the effects of American racism. The efforts of the latter category largely failed. In 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. described the layout of the landscape inside the Temple of Liberty:

One hundred years [after Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation], the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.

Exactly two months after King painted that portrait on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, the demolition of Penn Station began. Less than two months before King was assassinated, Madison Square Garden opened to the public. Just over thirty years later, Michael Jordan won his sixth and final NBA championship, and the Temple’s interior still conformed largely to King’s description. Jordan was living in the post civil-rights era and was himself a symbol of how much American culture had changed — for the better — since King’s death. But the decline of racial animosity had not bridged the chasm in living standards between America’s poorest and blackest urban neighborhoods, and our wealthiest and whitest. The chasm haunts us still.

One last dance. Urban architecture photographer Chris Hytha has captured this chasm vividly. His first major project was a series called “rowhomes,” and his second, which is ongoing, is called “highrises.” He photographed most of his rowhomes in Strawberry Mansion, which is a relatively poor and predominantly black neighborhood in North Philadelphia. He shot his highrises in the only places they tend to line the streets: bustling center city business districts. If highrises are a symbol of urban dynamism, Hytha’s rowhomes are perhaps a symbol of the price we paid to secure it, or at least the limits of its success.

The chasm between rowhome and highrise may not be a fundamental historical contradiction in the Fukuyaman sense. But at the very least it’s a jarring juxtaposition that lies at the very core of the American city in the twenty-first century. Twentieth-century efforts to bridge the chasm failed, and we seem largely to have accepted the failure as final. Our cities struggle to provide the most basic of municipal services and visionary leaders are nowhere to be found. In this sense we are living amid a different end of history — not only is the Temple of Liberty free of serious external challengers, but we’ve given up hope that its interior can be meaningfully improved. Those who lust for greatness do so only in a limited sense. At best we aspire, like Jordan, to be great only in some narrow domain and not in that of world history.

But the fact remains that never in human history has a culture confronted and conquered the challenge articulated by Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963. There are still regions hitherto unexplored. The question is whether the ambitious among us are up for the challenge. The fate of the United States rests upon the answer.

We can either bridge the chasm or be consumed by it.